Europeans Invade the Aztec Empire

Hernán Cortés and his company reached the island of San Juan de Ulúa on the coast of the Aztec province of Cuetlaxtlan (Veracruz) on April 20, 1519. Soon after, the Spaniards began exchanging messages with the ruler Motecuhzoma Xocoyotzin in Mexico-Tenochtitlan. From his interpreters, Jerónimo de Aguilar and Malintzin Tenepal, Cortés gained valuable information about the politics of the region, which he used to establish key political alliances necessary for achieving his goals. Language and knowledge thus became central to Spanish empire-building efforts in the lands dominated by the Aztecs.

Reports, maps, and specimens of all kinds were promptly dispatched to Spain along with the treasure collected by the conquistadors. For the Spaniards, the power to define the indigenous people—new subjects of the crown—equaled the right to rule them. The Nahuas too quickly understood that even their history and identity was itself a prized booty for the Spaniards.

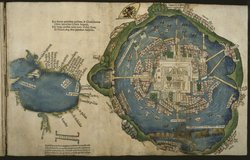

Newberry Library: Ayer 655.51 .C8 1524d

In his letters to the Hapsburg Emperor Charles V, King of Spain, Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés trumpeted his exploits, and described the people and wonders of the new land he had conquered. This map, published with Cortés’s letters, provided Europeans with the first image of the Aztec capital city, Tenochtitlan.

Although in ruins at the time of the map’s publication, the island city, with the Aztec sacred ceremonial district at its heart, appears serene and orderly under the double eagle and crown of the Hapsburg imperial flag. The smaller map to the left represents the Gulf of Mexico.

Newberry Library: Fitzgerald Map 2F G3290 1570.07 1580

First published in 1570, Ortelius’ map of America presents a Christianized image of Mexico (“Hispania Nova” or New Spain) and its cities and towns, many of which are represented by church towers and spires. Mexico-Tenuchtitlan (Tenochtitlan) is located on Lake Texcoco. A Dutchman, Ortelius dedicated his atlases to Philip II, King of Spain and the Netherlands.

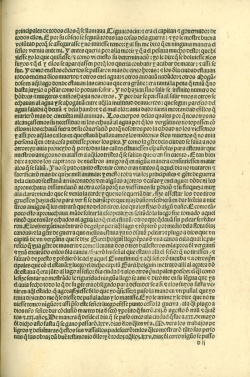

Newberry Library: Ayer 655.51 .C8 1523

Describing the last stages of the indigenous resistance in Tenochtitlan, Cortés confronted the human tragedy of the conquest. The conquistador was never able to predict or understand the Aztecs’ willingness to withstand misery, starvation, and massive deaths rather than surrender. Neither words nor the force of arms served him to persuade Cuauhtémoc, the last Aztec ruler, to submit to Spanish authority. How the world of the Indians was different from his was a question beyond his grasp.

Translation of transcription from Carta tercera de relación:

I welcomed him openly, so that he should not be afraid; but at last he told me that his sovereign would prefer to die where he was rather than on any account appear before me. . . . The people of the city had to walk upon their dead while others swam or drowned in the waters of that wide lake where they had their canoes; indeed, so great was their suffering that it was beyond our understanding how they could endure it. Countless numbers of men, women and children came out toward us, and in their eagerness to escape many were pushed into the water where they drowned amid that multitude of corpses; and it seemed that more than fifty thousand had perished from the salt water they had drunk, their hunger and the vile stench. So that we should not discover the plight which they were in, they dared neither throw these bodies into the water where the brigantines might find them nor throw them beyond their boundaries where the soldiers might see them; and so in those streets where they were, they came across such piles of the dead that we were forced to walk upon them (Cortés, Hernán. Letters from Mexico. Edited by Anthony Pagden. Translated by Anthony Pagden. New Haven London: Yale University Press, 1986, pp. 263-264.)

TIMELINE OF CONQUEST

February 18, 1519 Hernán Cortés departs from Cuba heading to Yucatan.

April 20, 1519 The conquistadors arrive at San Juan de Ulúa.

June 1519 The conquistadors found the town of Villa Rica de la Vera Cruz.

August 8, 1519 Cortés sets out for Tenochtitlan.

September 18, 1519 The conquistadors, after waging a violent war in the Tlaxcalan province, enter the city of Tlaxcala to establish an alliance with the indigenous leaders Maxixcatzin and Xicotencatl.

October 1519 The conquistadors massacre over one hundred unarmed Cholulan nobles in the courtyard of the Temple of Quetzalcoatl.

November 1519 Cortés meets the emperor, Motecuhzoma Xocoyotzin, near the entrance to Tenochtitlan, taking him prisoner shortly after.

May 1520 Pedro de Alvarado leads a massacre of indigenous nobles in Tenochtitlan during the festival of Toxcatl, causing a massive uprising.

July 1, 1520 The conquistadors escape Tenochtitlan under intense attack.

May 1521 Cortés initiates an attack on Tenochtitlan, besieging the city with the aid of thousands of allied indigenous troops.

August 1521 After leveling Tenochtitlan, the Spaniards finally capture the emperor, Cuauhtémoc, putting an end to Aztec resistance from within the city.

Newberry Library: Vault Ayer 111 .A5 1530

In 1522, the Italian humanist Pietro Martire d’Anghiera invited Juan de Ribera, Cortés's envoy from Mexico, to a gathering at his home. Meeting with a group of politically connected men from the Vatican, Venice, and Milan, Ribera answered questions about the indigenous civilization and showed them jewelry, crafts, clothing, maps, and other pictorial manuscripts. An Indian youngster demonstrated indigenous customs, performing military combat and courtly dances, and demonstrating ritual inebriation.

In 1530, d'Anghiera published De Orbe Nouo Decades. Based on Ribera’s report, the examination of indigenous items, and the Nahua boy’s performance, the book was the first serious depiction of Aztec civilization presented to European audiences.

Translation of Transcript from De Orbe Nouo Decades:

Among the maps of their land, we truly examined one that was thirty feet long, a little smaller in width, made of white woven cotton, in which all the plains with their provinces, both enemy and friendly to Motecuhzoma, were extensively inscribed. It shows at the same time vast mountains enclosing the plains all around and also the southern coasts, from whose inhabitants we heard that there are islands close to those shores where, as we said before, they grow great amounts of spices, gold and gems.

In those hills the inhabitants' accounts say there are wild men, shaggy as the furry bears of mountain dens and satisfied with filthy foods born in the earth or game. After the larger map, we saw another a little smaller, but with no less enthusiasm on our part, the very city of Tenochtitlan with its temples and bridges and surrounding lakes painted by indigenous hand. After this, [Ribera] had an indigenous youngster equipped as a warrior, whom he brought as his servant, come out from my room to the open terrace where we sat.

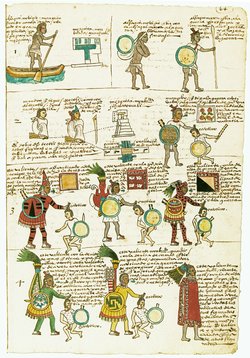

Newberry Library: Ayer folio F1219.56.C625 C64 1992

|

Indigenous painted books were a critical source for Spanish colonizers trying to understand the unfamiliar culture. Produced for Viceroy Antonio de Mendoza, the Codex Mendoza is a pictorial compilation that includes the imperial history of Tenochtitlan, tribute records, and a description of indigenous life from childhood to old age.

The top two lines of the page shown depict the training of a priest (which involved public works such as the repair of temples and bridges). The remaining images feature warriors, and illustrate the importance of war captives in the acquisition of social rank.

Newberry Library: Vault Ayer 108 .G6 1553 vol. 2

One of the most important sources on the Spanish conquest is Francisco López de Gómara’s Historia general de las Indias, the second section of which includes a detailed picture of indigenous culture and society in Mexico. Gómara worked with a wealth of sources, from previous accounts of the conquest to detailed studies of indigenous religion by missionaries in the field. Like most of his contemporaries, Gómara had difficulty grasping the breadth of indigenous learning. The various means of transmitting this knowledge were equally opaque to him.

Newberry Library: Vault Ayer 655.51 .D5 1632

Long after the conquest, the conquistadors continued to be haunted by their initial impressions of Tenochtitlan. As the Spaniards described their panoramic view of the city, this image evoked admiration, fear, and a desire to control the unknown.

Caught up in demands for grants and privileges, Bernal Díaz recalled the imposing image of the city from the Great Temple to justify the conquistadors’ violation of indigenous sovereignty. He described Motecuhzoma and Cortés, hands clasped, surveying the landscape before their eyes.

Newberry Library: Ayer F *655.51 .C8 1526

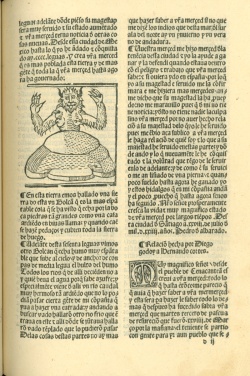

Early on, Spaniards identified indigenous gods with the Devil and used the concept of the Devil to convince indigenous people to abandon their traditional religious practices. Indians themselves embraced the European notion of the Devil and even used it ingeniously to challenge the imported religion.

A woodcut print of the Devil is included in Hernán Cortés’s Cuarta relación among notes regarding Pedro de Alvarado's recent invasion of Guatemala.