Auchagah’s Map

Karen Listette Eggermont

Pierre Margry, 1846 Tracing of original manuscript attributed to Auchagah ca. 1728-29.

Newberry Library Ayer Collection.

While at Fort Kaministikwia north of Lake Superior, Pierre Gaultier De Varennes de La Verendrye, a French army officer and explorer, requested Auchagah, a Cree Indian, to draw a map. Auchagah drew the map using a charcoal drawing by Tacchigis, another Cree, and also incorporated his own experience of the country. In addition, Auchagah added information from a map drawn by a third Cree Indian, La Marteblanche, “and two other chiefs of the same tribe.” Verendrye used this map to try to convince the French government that the River of the West—a Northwest Passage—existed and led to the Pacific, a strong argument for further French exploration in that direction.

The map shown here is a copy of a manuscript map attributed to Verendry, which was traced in 1846 by Pierre Margry, a clerk in a French archive trying to preserve the disintegrating original manuscript. Another transcription of Auchagah’s map by the French engineer Joseph Chaussegros de Lery (ca. 1730) is oriented south following Auchagah’s original.

Lawrence J. Burpee, ed., Journals and Letters of Pierre Gaultier de Varennes de La Verendrye and His Sons (Toronto: Champlain Society, 1927).

Edward Dahl and Conrad Heidenrich, “French Mapping of North America,” The Map Collector 19 (June 1982): 2-7.

Jean Delanglez, “Franquelin, Mapmaker,” Mid-America N.S. 14, 1 (January 1942): 29-74 and 17, 2 (April 1946): 67-144.

Malcolm Lewis, “La Grande Riviere et Flueve de L’Ouest: The Realities and Reasons Behind a Major Mistake in the Eighteenth-Century Geography of North America,” Cartographica 28, 1 (1991): 54-88.

Richard I. Ruggles and John Werkentin, eds., Manitoba Historical Atlas: A Selection of Facsimile Maps, Plans, and Sketches from 1612 to 1969 (Winnepeg: The Historical and Scientific Society of Manitoba, 1970).

Ronald Vere Tooley, French Mapping of the Americas (London: Map Collectors’ Circle, 1967).

NOTE: We are unable to reproduce an image of this map on the web.

Straight Lines in the Desert

Zur Shalev

Claudius Ptolemaeus, Cosmographia (Ulm: Leonhart Holle, 1486).

Newberry Library Ayer Collection

Cutting straight through complex social and geographical realities, geometrical boundary-lines tell us the story of the power of cartography in the shaping of the colonized and then de-colonized modern political theatre. Such lines over remote lands could have been stretched only by cartographically spirited minds, and surely, only with the aid of a map.

Cutting straight through complex social and geographical realities, geometrical boundary-lines tell us the story of the power of cartography in the shaping of the colonized and then de-colonized modern political theatre. Such lines over remote lands could have been stretched only by cartographically spirited minds, and surely, only with the aid of a map.

The case of Egypt, however, tells us another story as well, that of the long-term persistence of ideas and representations. Consider the shape of the present day Arab Republic of Egypt: both its western and its southern boundaries are almost perfect straight lines, defined by the abstract grid of parallels and meridians encapsulating the earth. Consider now the shape of Egypt (with Libya Marmarica) in the famous Ulm edition of Ptolemy’s Geography. Rectangular and defined by the grid, the second century Alexandrine’s Egypt, together with its Renaissance elaboration, is strikingly similar, conceptually and physically, to modern Egypt.

The British, Italian, and Ottoman diplomats who delineated the boundaries of Egypt at the beginning of the twentieth century were therefore not simply treating space as an abstract entity, amenable to rationalized partition. They were also, whether consciously or not, following a classical tradition of representation.

Samuel Y. Edgerton, “From Mental Matrix to Mappamundi to Christian Empire: The Heritage of Ptolemy’sGeography in the Renaissance,” in David Woodward, ed., Art and Cartography: Six Historical Essays (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987), pp. 10-50.

Michel Foucher, Fronts et Frontières: Un tour du monde géopolitique (Paris: Fayard, 1988).

Stephen B. Jones, Boundary-Making: A Handbook for Statesmen, Treaty Editors and Boundary Commissioners (Washington: Carnegie Endowment for Inter-national Peace, 1945).

Robert D. Sack, Human Territoriality: Its Theory and History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986).

R.A. Skelton, “Introduction,” in Claudius Ptolemy, Cosmographia, facsimile of the 1482 Ulm edition (Amsterdam: N. Israel, 1963).

Exploring Debate: Identity and Science in Maps of North America

John Vandevort Tarpley

UPPER: Joseph Nicholas de L’Isle, Carte Generale des Decouvertes De l’Amiral de Font Et autres Navigateurs Espagnols, Anglois, et Russes (Paris, 1752).

LOWER: G.F. Müller, A Map of the Discoveries made by the Russians on the North West Coast of America, Published by the Royal Academy of Sciences

at Petersburg (London: Carington Bowles, 1761).

Both from the Newberry Library Ayer Collection.

Eighteenth-century maps of North America reflect the loyalties and prejudices of the individual mapmakers as well as contemporary understandings of geography. Joseph Nicholas de L’Isle and Gerhard Friedrich Müller were both non-Russians who, due to their positions in the nascent Russian Academy of Sciences, had access to materials from recent Russian explorations of North America for the compilation of their maps. De L’Isle, however, combines the Russian data selectively with materials from apocryphal Spanish travel accounts and older maps championed by his brother in the tradition of “speculative cartography.” The resulting map depicts an extensive system of lakes and rivers in the western part of North America. De L’Isle’s map suggests his family loyalties and an ongoing European interest in finding the fabled Northwest Passage to Asia.

Eighteenth-century maps of North America reflect the loyalties and prejudices of the individual mapmakers as well as contemporary understandings of geography. Joseph Nicholas de L’Isle and Gerhard Friedrich Müller were both non-Russians who, due to their positions in the nascent Russian Academy of Sciences, had access to materials from recent Russian explorations of North America for the compilation of their maps. De L’Isle, however, combines the Russian data selectively with materials from apocryphal Spanish travel accounts and older maps championed by his brother in the tradition of “speculative cartography.” The resulting map depicts an extensive system of lakes and rivers in the western part of North America. De L’Isle’s map suggests his family loyalties and an ongoing European interest in finding the fabled Northwest Passage to Asia.

Müller, a Baltic German loyal to the Russian crown, asserts the authority of Russian imperial science in his map. As a proponent of empirical mapmaking, Müller pointedly dismisses the cartographic conjectures to which deIsle has subordinated Russian scientific efforts. Müller depicts no inland waterway, and marks with a solid line only parts of the North American continent seen by Russian sailors or found in other, “verified” European accounts.

Müller, a Baltic German loyal to the Russian crown, asserts the authority of Russian imperial science in his map. As a proponent of empirical mapmaking, Müller pointedly dismisses the cartographic conjectures to which deIsle has subordinated Russian scientific efforts. Müller depicts no inland waterway, and marks with a solid line only parts of the North American continent seen by Russian sailors or found in other, “verified” European accounts.

Alexei V. Postnikov, The Mapping of Russian America: A History of Russian-American Contacts in Cartography (Milwaukee: University of Wisconsin, 1995).

Henry R. Wagner, “Apocryphal Voyages to the Northwest Coast of America,” Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society, N.S. 41, 1 (1931): 179-234.

An Empire of the Sea

Joseph Cullon

TOP: “Chart of Boston Bay”

CENTER: “Boston, seen between Castle Williams and Governors Island, distant 4 Miles”

BOTTOM: “Appearence of the High Lands of Agameticus, N.E. with Penobscot Hills, to the Eastwards, at 3 to 4 Leagues off there”

All from J.F.W. DesBarres, The Atlantic Neptune, in the Newberry Library General Collections.

Looking toward Boston from London, the seat of the first British empire, these 1777 charts underscore the Atlantic context of the North American mainland colonies. Throughout the eighteenth century, imperial power rested as much upon control of the seas as upon territorial holdings and, in the Atlantic World, Britannia ruled the waves. Far exceeding in comprehensiveness, scale, accuracy, and beauty any previous English maps of the North American interior, these charts are a piece of the massive Atlantic Neptune, an atlas consisting of 178 individual charts, views, and text of the North American coast. Begun as part of Britain’s effort to consolidate its power after the expulsion of the French from Canada in 1763, the new atlas was the culmination of over a decade of exhaustive cartographic labor. This heroic project, however, only came to fruition in 1777 under the leadership of J.F.W. DesBarres, as the start of the American Revolution shattered Britain’s empire of the sea.

John Brewer, Sinews of Power: War, Money, and the English State, 1688-1783 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1990).

William Cumming, “The Colonial Charting of the Massachusetts Coast,” in Seafaring in Colonial Massachusetts (Boston: Colonial Society of Massachusetts, 1980).

G.H.D. Evans, Uncommon Obdurate: The Several Public Careers of J.F.W. DesBarres (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1969).

Taming the Northwestern Frontier

Cathleen D. Cahill

“The Northwest in 1900, Showing the North-Western System and Connecting Lines to the Pacific, also Indian Reservations and

their Population in 1899,” in The Indian, The Northwest, 1600-1900: The Red Man, The White Man and the Northwestern

Line (Chicago: Chicago & Northwestern Railway Co., 1901).

Newberry Library General Collection

This is the final map in a series illustrating a promotional booklet for the Chicago and North-Western Railway. Published in 1900, it is entitled “The Indian, The Northwest 1600-1900.” In it, the CNWRR put its own spin on a national myth of Western history-the inevitable decline of Indians in the face of American progress.

This is the final map in a series illustrating a promotional booklet for the Chicago and North-Western Railway. Published in 1900, it is entitled “The Indian, The Northwest 1600-1900.” In it, the CNWRR put its own spin on a national myth of Western history-the inevitable decline of Indians in the face of American progress.

The text of the booklet tells a sympathetic story of the Indians’ noble struggle, and at the same time, the maps graphically emphasize the railroad’s key role in western conquest. This use of maps muted what was a violent struggle into a peaceful shift of colors, conflating the story of shrinking Indian lands with the growing network of track. Limited to the northwestern portion of the United States, the map augments the CNWRR’s role over other lines. This version sanitized the history of the region, making it into a safe and historically significant space for tourism only a few decades after the Indian wars.

Anne Farrar Hyde, An American Vision: Far Western Landscapes and National Culture, 1820-1920 (New York: New York University Press, 1990).

Elliott West, The Contested Plains: Indians, Goldseekers, and the Rush to Colorado (Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas Press, 1999).

A Nation Made Easy

Douglas M. Bradburn

Jedidiah Morse, Geography Made Easy. Being a Short, but Comprehensive System of that very useful and agreeable Science (New Haven Connecticut, 1784).

Newberry Library Ayer Collection.

At the conclusion of the Revolutionary War, the newly independent Americans struggled to escape from the long shadow of British colonial identity and establish their legitimacy as a distinct nation. A major part of this process of self-discovery involved the encouragement of a homegrown excellence in the arts, letters, and sciences through the reform and expansion of the education of youth. Jedidiah Morse’s Geography Made Easy (1784), written to replace the “inadequate European Geographies” used before independence, represents an excellent example of the desire of the Founding Fathers to teach young Americans to recognize their uniqueness.

At the conclusion of the Revolutionary War, the newly independent Americans struggled to escape from the long shadow of British colonial identity and establish their legitimacy as a distinct nation. A major part of this process of self-discovery involved the encouragement of a homegrown excellence in the arts, letters, and sciences through the reform and expansion of the education of youth. Jedidiah Morse’s Geography Made Easy (1784), written to replace the “inadequate European Geographies” used before independence, represents an excellent example of the desire of the Founding Fathers to teach young Americans to recognize their uniqueness.

Intended for “the Use and Improvement of Schools in the United States,” Morse’s Geography sought not only to introduce students to the “useful and agreeable” science of geography, but to encourage Americans to “know the situation and boundaries of their own nation.” For, as Morse noted, citizens must be aware of the “character of their own country.” Complemented by a colorful map of the newly independent States of the Union and the requisite national myths surrounding George Washington and the War for Independence, the textbook readily encouraged students to imagine their distinctive nationhood.

This small volume dominated the market for children’s geography textbooks in America for over fifty years, and after twenty-five editions, easily secured Morse’s reputation as the “Father of American Geography.”

Martin Brückner, “Lessons in Geography: Maps, Spellers, and Other Grammars of Nationalism in the Early Republic,” American Quarterly 51, 2 (June 1999): 311-343.

All Roads Lead to Chicago

Laura Milsk

“Birdseye View of the Chicago Railway System,” in 7 Days in Chicago: A Complete Guide to the Street Cars, Omnibuses, Railroads, Notable Buildings, Union Stockyrads, Churches, Charitable Institutions, Etc. (Chicago: J.M. Wing & Co., 1877).

Newberry Library John M. Wing Foundation Collection.

This “Guide to Chicago’s Railroads” appeared in a travel booklet published by Rand, McNally & Co., in 1877. In this unusual orientation, the observer is looking at the Gem of the Prairie and her railway system from the west. The railroads here are actively joining isolated settlements to one another and the marketplace of Chicago, pictured here as a jagged city on the shores of an idyllic lake. All of the trains are heading into the city bringing not only goods, but also linking the distant West with the settled East. The ships on the water may come and go to unknown ports, but the railroads clearly accomplish their objective—transporting the economy of the West to Chicago. In the end, two vast regions, East and West, are accessible only through the unifying force of the railroads that connect in the “Great Metropolis of the West.”

This “Guide to Chicago’s Railroads” appeared in a travel booklet published by Rand, McNally & Co., in 1877. In this unusual orientation, the observer is looking at the Gem of the Prairie and her railway system from the west. The railroads here are actively joining isolated settlements to one another and the marketplace of Chicago, pictured here as a jagged city on the shores of an idyllic lake. All of the trains are heading into the city bringing not only goods, but also linking the distant West with the settled East. The ships on the water may come and go to unknown ports, but the railroads clearly accomplish their objective—transporting the economy of the West to Chicago. In the end, two vast regions, East and West, are accessible only through the unifying force of the railroads that connect in the “Great Metropolis of the West.”

Carl Abbott, Boosters and Businessmen: Popular Economic Thought and Urban Growth in the Antebellum Midwest (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1981).

William Cronon, Nature’s Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West (New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 1992).

Sarah Gordon, Passage to Union: How the Railroads Transformed American Life, 1829-1929 (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 1997).

Imagining France

Elisabeth Hodges

Sebastion Münster, Plan of Paris from Cosmographie universalle de tout le monde.... François de Belleforest, ed. (Bâle: Chez Michel Sonnius, 1575).

Newberry Library General Collection.

Well before modern notions of nationhood were firmly established, city views and descriptions of Paris offered a way for the public to think about Frenchness. At the time this image of Paris began to circulate in the 1570s, the city had already acquired a reputation as a growing metropolitan center, rich in commerce and fluvial trade, and as early as 1525 the city had become the official residence of the French monarchy. In François de Belleforest’s edition of Münster’s Cosmographie universelle of 1575, the viewer’s gaze scans eastward as it replicates a historical itinerary through Paris, traversing the city from its Roman origins on the islands at the center of the Seine river, through the bustling avenues slicing up housing blocks, to the recently established settlements outside the old city walls. This view provides a vision of the city as a whole depicted from an imaginary bird’s-eye perspective, as well as an urban landscape replete with architectural details and monuments emerging from the city streets. Cartouches occupy the rural landscape beyond the city walls and symbolically link the experience of walking through the city with the French monarchy. Rich in its historical and cultural importance, Paris plays an important role in making France and in imagining the nation.

Numa Broc, La Géographie de la Renaissance (Paris: Les Editions du C.T.H.S., 1986).

Michel de Certeau, L’Invention du quotidien. I. Arts de faire (Paris: Folio, 1990).

Tom Conley, The Self-Made Map: Cartographic Writing in Early Modern France (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1996).

Christian Jacob, L’Empire des cartes. Approche théorique de la cartographie á travers l’histoire (Paris: Albin, 1992).

Mapping the American Dream

Christopher J. DiMaggio

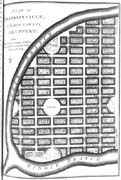

“Plan of Franklinville, in Mason County, Kentucky,” from An Historical, Geographical, Commercial and Philosophical View of the United States, and of the European Settlements in America and the West Indies (London, 1795).

Newberry Library Ayer Collection.

Franklinville, Kentucky, does not exist, except in this 1795 plan by William Winterbotham. The mapping of such speculative paper towns was an important part of the westward expansion of the United States. Some of these “cities on paper” were artful boondoggles meant to separate heedless investors from their money. Others, such as Cincinnati, in time lived up to their promises. But many, like Franklinville, fell somewhere in-between; drawn with the best intentions, they perhaps became minor towns or suburbs, if they were built at all.

Franklinville, Kentucky, does not exist, except in this 1795 plan by William Winterbotham. The mapping of such speculative paper towns was an important part of the westward expansion of the United States. Some of these “cities on paper” were artful boondoggles meant to separate heedless investors from their money. Others, such as Cincinnati, in time lived up to their promises. But many, like Franklinville, fell somewhere in-between; drawn with the best intentions, they perhaps became minor towns or suburbs, if they were built at all.

Winterbotham’s plan stands at the beginning of American town planning, a process by which diverse groups of Americans came to terms with their place in the American landscape. Mapping an efficient, beautiful, and orderly city would later be a goal of new utopian and religious communities in the late 1800s.

Daniel C. Hammack, “Comprehensive Planning Before the Comprehensive Plan: A New Look at the Nineteenth-Century American City,” in Daniel Schaffer, ed., Two Centuries of American Planning (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1988).

John W. Reps, The Making of Urban America: A History of City Planning in the United States (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1965).

Stanley K. Schultz, Constructing Urban Culture: American Cities and City Planning, 1800-1920 (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1989).

Views of Rome: Monuments of Church and Empire

Felicia M. Else

TOP: Antonio Lafréry and Stephano Du Perac, Pianta di Roma from Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae (Rome, 1573).

BOTTOM: Antonio Lafréry, Seven Churches of Rome (Rome 1575).

Both from the Newberry Library Novacco Collection.

These two views of Rome picture representations of architectural monuments that embody the institutions of Roman power: ancient imperial Rome and the papacy. Both engravings come from the celebrated workshop of Antonio Lafréry during the pontificate of Gregory XIII—a time of urban renewal and militant church reform.

These two views of Rome picture representations of architectural monuments that embody the institutions of Roman power: ancient imperial Rome and the papacy. Both engravings come from the celebrated workshop of Antonio Lafréry during the pontificate of Gregory XIII—a time of urban renewal and militant church reform.

The 1573 view of Rome shows a re-creation of the ancient city based on literary texts and archaeological ruins, identifying such monuments as the Pantheon and Colosseum. The achievements of imperial Rome served as models to architects and urban planners in the building of aqueducts, roads, and palaces, and to political leaders in the acquisition of territory and the display of triumphal power. This “map” of ancient Rome appealed to scholars and antiquarians, forming the opening pages of the Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae, a collection of engravings of ancient and contemporary buildings and statuary, including Michelangelo’s plan for St. Peter’s cathedral.

The 1575 Seven Churches of Rome celebrates the power of papal authority in the depiction of pilgrims reverently visiting the city’s principal churches. Lafréry renders these buildings in meticulous detail on an exaggerated scale, choosing an unusual vantage point and altering the orientation of St. Peter’s to emphasize its facade. The print commemorates a Jubilee, a special festival year for visiting pilgrims to receive additional indulgences. Each church is accompanied by its patron saint, reinforcing the cult of relics and the authority of St. Peter during a time marked by the Inquisition and Reformation dissent.

The 1575 Seven Churches of Rome celebrates the power of papal authority in the depiction of pilgrims reverently visiting the city’s principal churches. Lafréry renders these buildings in meticulous detail on an exaggerated scale, choosing an unusual vantage point and altering the orientation of St. Peter’s to emphasize its facade. The print commemorates a Jubilee, a special festival year for visiting pilgrims to receive additional indulgences. Each church is accompanied by its patron saint, reinforcing the cult of relics and the authority of St. Peter during a time marked by the Inquisition and Reformation dissent.

Amato Pietro Frutaz, Le piante di Roma (Rome: Istituto di studi romani, 1962).

Christopher Hibbert, Rome, the Biography of a City (London: Viking, 1985).

David Woodward, Maps as Prints in the Italian Renaissance: Makers, Distributors and Consumers (London: The British Library, 1996).

Framing a Nation

Davide Papotti

Giacomo Gastaldi, Il Disegno Della Geografia Moderna de Tutta la Provincia de la Italia.... (Venice: Fabio Licinio, 1561).

Newberry Library Novacco Collection.

This map, drawn by Giacomo (or Jacopo) Gastaldi, one of the most important cartographers of sixteenth-century Italy, is an example of the high quality of artifacts produced by the Venetian engraving laboratories. The map represents the Italian region (Italy was not unified as a state until 1861-three centuries later) in its entirety with the exception of parts of the islands of Sicily and Sardinia and of the northeastern part of the Alps. This particular perspective is a heritage from the Ptolemaic cartographic tradition, but the “frame” of the peninsula also functions to celebrate Venice and its dominions: it emphasizes the centrality of the Adriatic Sea, here meaningfully renamed the “Venetian Gulf,” and provides an accurate portrait of the Dalmatian coast, where Venice had commercial activities. The definition of the “frame” of the map, therefore, silently conveys to the reader a political message about the centrality of Venice in the Italian geographical context.

This map, drawn by Giacomo (or Jacopo) Gastaldi, one of the most important cartographers of sixteenth-century Italy, is an example of the high quality of artifacts produced by the Venetian engraving laboratories. The map represents the Italian region (Italy was not unified as a state until 1861-three centuries later) in its entirety with the exception of parts of the islands of Sicily and Sardinia and of the northeastern part of the Alps. This particular perspective is a heritage from the Ptolemaic cartographic tradition, but the “frame” of the peninsula also functions to celebrate Venice and its dominions: it emphasizes the centrality of the Adriatic Sea, here meaningfully renamed the “Venetian Gulf,” and provides an accurate portrait of the Dalmatian coast, where Venice had commercial activities. The definition of the “frame” of the map, therefore, silently conveys to the reader a political message about the centrality of Venice in the Italian geographical context.

Roberto Almagiá, Monumenta Italiae Cartographica: Riproduzione di carte generali e regionali d'Italia dal secolo XIV al XVII (Firenze: Istituto Geografico Militare, 1929).

John Marino, “Administrative Mapping in the Italian States,” in David Buisseret, ed., Monarchs, Ministers, and Maps: The Emergence of Cartography as a Tool of Government in Early Modern Europe (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992), pp. 5-25.

David Woodward, Maps as Prints in the Italian Renaissance: Makers, Distributors and Consumers (London: The British Library, 1996).